mirror of

https://github.com/ClickHouse/ClickHouse.git

synced 2024-11-27 10:02:01 +00:00

355 lines

34 KiB

Markdown

355 lines

34 KiB

Markdown

## clickhouse-obfuscator — a tool for dataset anonymization

|

||

|

||

### Installation And Usage

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

curl https://clickhouse.com/ | sh

|

||

./clickhouse obfuscator --help

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Example

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

./clickhouse obfuscator --seed 123 --input-format TSV --output-format TSV \

|

||

--structure 'CounterID UInt32, URLDomain String, URL String, SearchPhrase String, Title String' \

|

||

< source.tsv > result.tsv

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

|

||

### A long, long time ago...

|

||

|

||

ClickHouse users already know that its biggest advantage is its high-speed processing of analytical queries. But claims like this need to be confirmed with reliable performance testing. That's what we want to talk about today.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

We started running tests in 2013, long before ClickHouse was available as open source. Back then, our main concern was data processing speed for a web analytics product. We started storing this data, which we would later store in ClickHouse, in January 2009. Part of the data had been written to a database starting in 2012, and part was converted from OLAPServer and Metrage (data structures previously used by the solution). For testing, we took the first subset at random from data for 1 billion pageviews. Our web analytics platform didn't have any queries at that point, so we came up with queries that interested us, using all the possible ways to filter, aggregate, and sort the data.

|

||

|

||

ClickHouse performance was compared with similar systems like Vertica and MonetDB. To avoid bias, testing was performed by an employee who hadn't participated in ClickHouse development, and special cases in the code were not optimized until all the results were obtained. We used the same approach to get a data set for functional testing.

|

||

|

||

After ClickHouse was released as open source in 2016, people began questioning these tests.

|

||

|

||

## Shortcomings of tests on private data

|

||

|

||

Our performance tests:

|

||

|

||

- Couldn't be reproduced independently because they used private data that can't be published. Some of the functional tests are not available to external users for the same reason.

|

||

- Needed further development. The set of tests needed to be substantially expanded in order to isolate performance changes in individual parts of the system.

|

||

- Didn't run on a per-commit basis or for individual pull requests. External developers couldn't check their code for performance regressions.

|

||

|

||

We could solve these problems by throwing out the old tests and writing new ones based on open data, like [flight data for the USA](https://clickhouse.com/docs/en/getting-started/example-datasets/ontime/) and [taxi rides in New York](https://clickhouse.com/docs/en/getting-started/example-datasets/nyc-taxi). Or we could use benchmarks like TPC-H, TPC-DS, and [Star Schema Benchmark](https://clickhouse.com/docs/en/getting-started/example-datasets/star-schema). The disadvantage is that this data was very different from web analytics data, and we would rather keep the test queries.

|

||

|

||

### Why it's important to use real data

|

||

|

||

Performance should only be tested on real data from a production environment. Let's look at some examples.

|

||

|

||

### Example 1

|

||

|

||

Let's say you fill a database with evenly distributed pseudorandom numbers. Data compression isn't going to work in this case, although data compression is essential to analytical databases. There is no silver bullet solution to the challenge of choosing the right compression algorithm and the right way to integrate it into the system since data compression requires a compromise between the speed of compression and decompression and the potential compression efficiency. But systems that can't compress data are guaranteed losers. If your tests use evenly distributed pseudorandom numbers, this factor is ignored, and the results will be distorted.

|

||

|

||

Bottom line: Test data must have a realistic compression ratio.

|

||

|

||

### Example 2

|

||

|

||

Let's say we are interested in the execution speed of this SQL query:

|

||

|

||

```sql

|

||

SELECT RegionID, uniq(UserID) AS visitors

|

||

FROM test.hits

|

||

GROUP BY RegionID

|

||

ORDER BY visitors DESC

|

||

LIMIT 10

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

This was a typical query for web analytics product. What affects the processing speed?

|

||

|

||

- How `GROUP BY` is executed.

|

||

- Which data structure is used for calculating the `uniq` aggregate function.

|

||

- How many different RegionIDs there are and how much RAM each state of the `uniq` function requires.

|

||

|

||

But another important factor is that the amount of data is distributed unevenly between regions. (It probably follows a power law. I put the distribution on a log-log graph, but I can't say for sure.) If this is the case, the states of the `uniq` aggregate function with fewer values must use very little memory. When there are a lot of different aggregation keys, every single byte counts. How can we get generated data that has all these properties? The obvious solution is to use real data.

|

||

|

||

Many DBMSs implement the HyperLogLog data structure for an approximation of COUNT(DISTINCT), but none of them work very well because this data structure uses a fixed amount of memory. ClickHouse has a function that uses [a combination of three different data structures](https://clickhouse.com/docs/en/sql-reference/aggregate-functions/reference/uniqcombined), depending on the size of the data set.

|

||

|

||

Bottom line: Test data must represent distribution properties of the real data well enough, meaning cardinality (number of distinct values per column) and cross-column cardinality (number of different values counted across several different columns).

|

||

|

||

### Example 3

|

||

|

||

Instead of testing the performance of the ClickHouse DBMS, let's take something simpler, like hash tables. For hash tables, it's essential to choose the right hash function. This is not as important for `std::unordered_map`, because it's a hash table based on chaining, and a prime number is used as the array size. The standard library implementation in GCC and Clang uses a trivial hash function as the default hash function for numeric types. However, `std::unordered_map` is not the best choice when we are looking for maximum speed. With an open-addressing hash table, we can't just use a standard hash function. Choosing the right hash function becomes the deciding factor.

|

||

|

||

It's easy to find hash table performance tests using random data that don't take the hash functions used into account. Many hash function tests also focus on the calculation speed and certain quality criteria, even though they ignore the data structures used. But the fact is that hash tables and HyperLogLog require different hash function quality criteria.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

## Challenge

|

||

|

||

Our goal was to obtain data for testing performance that had the same structure as our web analytics data with all the properties that are important for benchmarks, but in such a way that there remain no traces of real website users in this data. In other words, the data must be anonymized and still preserve its:

|

||

|

||

* Compression ratio.

|

||

* Cardinality (the number of distinct values).

|

||

* Mutual cardinality between several different columns.

|

||

* Properties of probability distributions that can be used for data modeling (for example, if we believe that regions are distributed according to a power law, then the exponent — the distribution parameter — should be approximately the same for artificial data and for real data).

|

||

|

||

How can we get a similar compression ratio for the data? If LZ4 is used, substrings in binary data must be repeated at approximately the same distance, and the repetitions must be approximately the same length. For ZSTD, entropy per byte must also coincide.

|

||

|

||

The ultimate goal was to create a publicly available tool that anyone can use to anonymize their data sets for publication. This would allow us to debug and test performance on other people's data similar to our production data. We would also like the generated data to be interesting.

|

||

|

||

However, these are very loosely-defined requirements, and we aren't planning to write up a formal problem statement or specification for this task.

|

||

|

||

## Possible solutions

|

||

|

||

I don't want to make it sound like this problem was particularly important. It was never actually included in planning, and no one had intentions to work on it. I hoped that an idea would come up someday, and suddenly I would be in a good mood and be able to put everything else off until later.

|

||

|

||

### Explicit probabilistic models

|

||

|

||

- We want to preserve the continuity of time series data. This means that for some types of data, we need to model the difference between neighboring values rather than the value itself.

|

||

- To model "joint cardinality" of columns, we would also have to explicitly reflect dependencies between columns. For instance, there are usually very few IP addresses per user ID, so to generate an IP address, we would have to use a hash value of the user ID as a seed and add a small amount of other pseudorandom data.

|

||

- We weren't sure how to express the dependency that the same user frequently visits URLs with matching domains at approximately the same time.

|

||

|

||

All this can be written in a C++ "script" with the distributions and dependencies hard coded. However, Markov models are obtained from a combination of statistics with smoothing and adding noise. I started writing a script like this, but after writing explicit models for ten columns, it became unbearably boring — and the "hits" table in the web analytics product had more than 100 columns way back in 2012.

|

||

|

||

```c++

|

||

EventTime.day(std::discrete_distribution<>({

|

||

0, 0, 13, 30, 0, 14, 42, 5, 6, 31, 17, 0, 0, 0, 0, 23, 10, ...})(random));

|

||

EventTime.hour(std::discrete_distribution<>({

|

||

13, 7, 4, 3, 2, 3, 4, 6, 10, 16, 20, 23, 24, 23, 18, 19, 19, ...})(random));

|

||

EventTime.minute(std::uniform_int_distribution<UInt8>(0, 59)(random));

|

||

EventTime.second(std::uniform_int_distribution<UInt8>(0, 59)(random));

|

||

|

||

UInt64 UserID = hash(4, powerLaw(5000, 1.1));

|

||

UserID = UserID / 10000000000ULL * 10000000000ULL

|

||

+ static_cast<time_t>(EventTime) + UserID % 1000000;

|

||

|

||

random_with_seed.seed(powerLaw(5000, 1.1));

|

||

auto get_random_with_seed = [&]{ return random_with_seed(); };

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Advantages:

|

||

|

||

- Conceptual simplicity.

|

||

|

||

Disadvantages:

|

||

|

||

- A large amount of work is required.

|

||

- The solution only applies to one type of data.

|

||

|

||

And I preferred a more general solution that can be used for obfuscating any dataset.

|

||

|

||

In any case, this solution could be improved. Instead of manually selecting models, we could implement a catalog of models and choose the best among them (best fit plus some form of regularization). Or maybe we could use Markov models for all types of fields, not just for text. Dependencies between data could also be extracted automatically. This would require calculating the [relative entropy](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kullback%E2%80%93Leibler_divergence) (the relative amount of information) between columns. A simpler alternative is to calculate relative cardinalities for each pair of columns (something like "how many different values of A are there on average for a fixed value B"). For instance, this will make it clear that `URLDomain` fully depends on the `URL`, and not vice versa.

|

||

|

||

But I also rejected this idea because there are too many factors to consider, and it would take too long to write.

|

||

|

||

### Neural networks

|

||

|

||

As I've already mentioned, this task wasn't high on the priority list — no one was even thinking about trying to solve it. But as luck would have it, our colleague Ivan Puzirevsky was teaching at the Higher School of Economics. He asked me if I had any interesting problems that would work as suitable thesis topics for his students. When I offered him this one, he assured me it had potential. So I handed this challenge off to a nice guy "off the street" Sharif (he did have to sign an NDA to access the data, though).

|

||

|

||

I shared all my ideas with him but emphasized that there were no restrictions on how the problem could be solved, and a good option would be to try approaches that I know nothing about, like using LSTM to generate a text dump of data. This seemed promising after coming across the article [The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks](http://karpathy.github.io/2015/05/21/rnn-effectiveness/).

|

||

|

||

The first challenge is that we need to generate structured data, not just text. But it wasn't clear whether a recurrent neural network could generate data with the desired structure. There are two ways to solve this. The first solution is to use separate models for generating the structure and the "filler", and only use the neural network for generating values. But this approach was postponed and then never completed. The second solution is to simply generate a TSV dump as text. Experience has shown that some of the rows in the text won't match the structure, but these rows can be thrown out when loading the data.

|

||

|

||

The second challenge is that the recurrent neural network generates a sequence of data, and thus dependencies in data must follow in the order of the sequence. But in our data, the order of columns can potentially be in reverse to dependencies between them. We didn't do anything to resolve this problem.

|

||

|

||

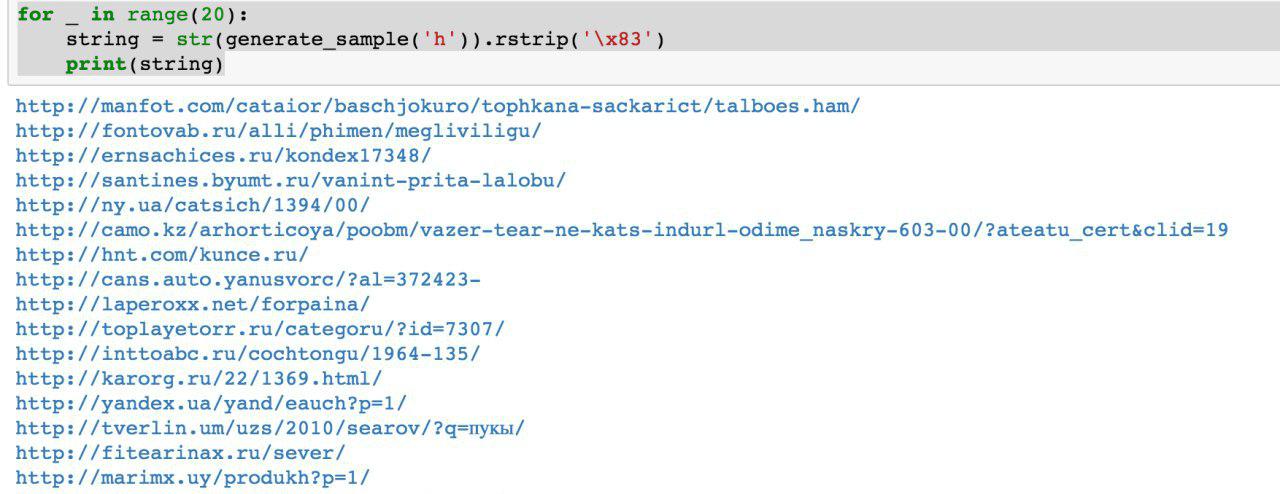

As summer approached, we had the first working Python script that generated data. The data quality seemed decent at first glance:

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

However, we did run into some difficulties:

|

||

|

||

1. The size of the model was about a gigabyte. We tried to create a model for data that was several gigabytes in size (for a start). The fact that the resulting model is so large raised concerns. Would it be possible to extract the real data that it was trained on? Unlikely. But I don't know much about machine learning and neural networks, and I haven't read this developer's Python code, so how can I be sure? There were several articles published at the time about how to compress neural networks without loss of quality, but it wasn't implemented. On the one hand, this doesn't seem to be a serious problem since we can opt out of publishing the model and just publish the generated data. On the other hand, if overfitting occurs, the generated data may contain some part of the source data.

|

||

|

||

2. On a machine with a single CPU, the data generation speed is approximately 100 rows per second. Our goal was to generate at least a billion rows. Calculations showed that this wouldn't be completed before the date of the thesis defense. It didn't make sense to use additional hardware because the goal was to make a data generation tool that anyone could use.

|

||

|

||

Sharif tried to analyze the quality of data by comparing statistics. Among other things, he calculated the frequency of different characters occurring in the source data and in the generated data. The result was stunning: the most frequent characters were Ð and Ñ.

|

||

|

||

Don't worry about Sharif, though. He successfully defended his thesis, and we happily forgot about the whole thing.

|

||

|

||

### Mutation of compressed data

|

||

|

||

Let's assume that the problem statement has been reduced to a single point: we need to generate data that has the same compression ratio as the source data, and the data must decompress at the same speed. How can we achieve this? We need to edit compressed data bytes directly! This allows us to change the data without changing the size of the compressed data, plus everything will work fast. I wanted to try out this idea right away, despite the fact that the problem it solves is different from what we started with. But that's how it always is.

|

||

|

||

So how do we edit a compressed file? Let's say we are only interested in LZ4. LZ4 compressed data is composed of sequences, which in turn are strings of not-compressed bytes (literals), followed by a match copy:

|

||

|

||

1. Literals (copy the following N bytes as is).

|

||

2. Matches with a minimum repeat length of 4 (repeat N bytes in the file at a distance of M).

|

||

|

||

Source data:

|

||

|

||

`Hello world Hello.`

|

||

|

||

Compressed data (arbitrary example):

|

||

|

||

`literals 12 "Hello world " match 5 12.`

|

||

|

||

In the compressed file, we leave "match" as-is and change the byte values in "literals". As a result, after decompressing, we get a file in which all repeating sequences at least 4 bytes long are also repeated at the same distance, but they consist of a different set of bytes (basically, the modified file doesn't contain a single byte that was taken from the source file).

|

||

|

||

But how do we change the bytes? The answer isn't obvious because, in addition to the column types, the data also has its own internal, implicit structure that we would like to preserve. For example, text data is often stored in UTF-8 encoding, and we want the generated data also to be valid UTF-8. I developed a simple heuristic that involves meeting several criteria:

|

||

|

||

- Null bytes and ASCII control characters are kept as-is.

|

||

- Some punctuation characters remain as-is.

|

||

- ASCII is converted to ASCII, and for everything else, the most significant bit is preserved (or an explicit set of "if" statements is written for different UTF-8 lengths). In one byte class, a new value is picked uniformly at random.

|

||

- Fragments like `https://` are preserved; otherwise, it looks a bit silly.

|

||

|

||

The only caveat to this approach is that the data model is the source data itself, which means it cannot be published. The model is only fit for generating amounts of data no larger than the source. On the contrary, the previous approaches provide models allowing the generation of data of arbitrary size.

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwpgafe/klwlpm&qw=962788775I0E7bs7OXeAyAx

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwdffhant.am/wcpoyodjit/cbytjgeoocvdtclac

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwpgafe/klwlpm&qw=962788775I0E7bs7OXe

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwdffhant.am/wcpoyodjit/cbytjgeoocvdtclac

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwdbknvj.s/hmqhpsavon.yf#aortxqdvjja

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqw-bknvj.s/hmqhpsavon.yf#aortxqdvjja

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwpdtu-Unu-Rjanjna-bbcohu_qxht

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqw-bknvj.s/hmqhpsavon.yf#aortxqdvjja

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwpdtu-Unu-Rjanjna-bbcohu_qxht

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqw-bknvj.s/hmqhpsavon.yf#aortxqdvjja

|

||

http://ljc.she/kdoqdqwpdtu-Unu-Rjanjna-bbcohu-702130

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The results were positive, and the data was interesting, but something wasn't quite right. The URLs kept the same structure, but in some of them, it was too easy to recognize the original terms, such as "avito" (a popular marketplace in Russia), so I created a heuristic that swapped some of the bytes around.

|

||

|

||

There were other concerns as well. For example, sensitive information could possibly reside in a FixedString column in binary representation and potentially consist of ASCII control characters and punctuation, which I decided to preserve. However, I didn't take data types into consideration.

|

||

|

||

Another problem is that if a column stores data in the "length, value" format (this is how String columns are stored), how do I ensure that the length remains correct after the mutation? When I tried to fix this, I immediately lost interest.

|

||

|

||

### Random permutations

|

||

|

||

Unfortunately, the problem wasn't solved. We performed a few experiments, and it just got worse. The only thing left was to sit around doing nothing and surf the web randomly since the magic was gone. Luckily, I came across a page that [explained the algorithm](http://fabiensanglard.net/fizzlefade/index.php) for rendering the death of the main character in the game Wolfenstein 3D.

|

||

|

||

<img src="https://clickhouse.com/uploads/wolfenstein_bb259bd741.gif" alt="wolfenstein.gif" style="width: 764px;">

|

||

|

||

<br/>

|

||

|

||

The animation is really well done — the screen fills up with blood. The article explains that this is actually a pseudorandom permutation. A random permutation of a set of elements is a randomly picked bijective (one-to-one) transformation of the set. In other words, a mapping where each and every derived element corresponds to exactly one original element (and vice versa). In other words, it is a way to randomly iterate through all the elements of a data set. And that is exactly the process shown in the picture: each pixel is filled in random order, without any repetition. If we were to just choose a random pixel at each step, it would take a long time to get to the last one.

|

||

|

||

The game uses a very simple algorithm for pseudorandom permutation called linear feedback shift register ([LFSR](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linear-feedback_shift_register)). Similar to pseudorandom number generators, random permutations, or rather their families, can be cryptographically strong when parametrized by a key. This is exactly what we needed for our data transformation. However, the details were trickier. For example, cryptographically strong encryption of N bytes to N bytes with a pre-determined key and initialization vector seems like it would work for a pseudorandom permutation of a set of N-byte strings. Indeed, this is a one-to-one transformation, and it appears to be random. But if we use the same transformation for all of our data, the result may be susceptible to cryptoanalysis because the same initialization vector and key value are used multiple times. This is similar to the [Electronic Codebook](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation#ECB) mode of operation for a block cipher.

|

||

|

||

For example, three multiplications and two xorshift operations are used for the [murmurhash](https://github.com/ClickHouse/ClickHouse/blob/master/dbms/src/Common/HashTable/Hash.h#L18) finalizer. This operation is a pseudorandom permutation. However, I should point out that hash functions don't have to be one-to-one (even hashes of N bits to N bits).

|

||

|

||

Or here's another interesting [example from elementary number theory](https://preshing.com/20121224/how-to-generate-a-sequence-of-unique-random-integers/) from Jeff Preshing's website.

|

||

|

||

How can we use pseudorandom permutations to solve our problem? We can use them to transform all numeric fields so we can preserve the cardinalities and mutual cardinalities of all combinations of fields. In other words, COUNT(DISTINCT) will return the same value as before the transformation and, furthermore, with any GROUP BY.

|

||

|

||

It is worth noting that preserving all cardinalities somewhat contradicts our goal of data anonymization. Let's say someone knows that the source data for site sessions contains a user who visited sites from 10 different countries, and they want to find that user in the transformed data. The transformed data also shows that the user visited sites from 10 different countries, which makes it easy to narrow down the search. However, even if they find out what the user was transformed into, it won't be very useful; all of the other data has also been transformed, so they won't be able to figure out what sites the user visited or anything else. But these rules can be applied in a chain. For example, suppose someone knows that the most frequently occurring website in our data is Google, with Yahoo in second place. In that case, they can use the ranking to determine which transformed site identifiers actually mean Yahoo and Google. There's nothing surprising about this since we are working with an informal problem statement, and we are trying to find a balance between the anonymization of data (hiding information) and preserving data properties (disclosure of information). For information about how to approach the data anonymization issue more reliably, read this [article](https://medium.com/georgian-impact-blog/a-brief-introduction-to-differential-privacy-eacf8722283b).

|

||

|

||

In addition to keeping the original cardinality of values, I also wanted to keep the order of magnitude of the values. What I mean is that if the source data contained numbers under 10, then I want the transformed numbers to also be small. How can we achieve this?

|

||

|

||

For example, we can divide a set of possible values into size classes and perform permutations within each class separately (maintaining the size classes). The easiest way to do this is to take the nearest power of two or the position of the most significant bit in the number as the size class (these are the same thing). The numbers 0 and 1 will always remain as is. The numbers 2 and 3 will sometimes remain as is (with a probability of 1/2) and will sometimes be swapped (with a probability of 1/2). The set of numbers 1024..2047 will be mapped to one of 1024! (factorial) variants, and so on. For signed numbers, we will keep the sign.

|

||

|

||

It's also doubtful whether we need a one-to-one function. We can probably just use a cryptographically strong hash function. The transformation won't be one-to-one, but the cardinality will be close to the same.

|

||

|

||

However, we need a cryptographically strong random permutation so that when we define a key and derive a permutation with that key, restoring the original data from the rearranged data without knowing the key would be difficult.

|

||

|

||

There is one problem: in addition to knowing nothing about neural networks and machine learning, I am also quite ignorant when it comes to cryptography. That leaves just my courage. I was still reading random web pages and found a link on [Hackers News](https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=15122540) to a discussion on Fabien Sanglard's page. It had a link to a [blog post](http://antirez.com/news/113) by Redis developer Salvatore Sanfilippo that talked about using a wonderful generic way of getting random permutations, known as a [Feistel network](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feistel_cipher).

|

||

|

||

The Feistel network is iterative, consisting of rounds. Each round is a remarkable transformation that allows you to get a one-to-one function from any function. Let's look at how it works.

|

||

|

||

1. The argument's bits are divided into two halves:

|

||

```

|

||

arg: xxxxyyyy

|

||

arg_l: xxxx

|

||

arg_r: yyyy

|

||

```

|

||

2. The right half replaces the left. In its place, we put the result of XOR on the initial value of the left half and the result of the function applied to the initial value of the right half, like this:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

res: yyyyzzzz

|

||

res_l = yyyy = arg_r

|

||

res_r = zzzz = arg_l ^ F(arg_r)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

There is also a claim that if we use a cryptographically strong pseudorandom function for F and apply a Feistel round at least four times, we'll get a cryptographically strong pseudorandom permutation.

|

||

|

||

This is like a miracle: we take a function that produces random garbage based on data, insert it into the Feistel network, and we now have a function that produces random garbage based on data, but yet is invertible!

|

||

|

||

The Feistel network is at the heart of several data encryption algorithms. What we're going to do is something like encryption, only it's really bad. There are two reasons for this:

|

||

|

||

1. We are encrypting individual values independently and in the same way, similar to the Electronic Codebook mode of operation.

|

||

2. We are storing information about the order of magnitude (the nearest power of two) and the sign of the value, which means that some values do not change at all.

|

||

|

||

This way, we can obfuscate numeric fields while preserving the properties we need. For example, after using LZ4, the compression ratio should remain approximately the same because the duplicate values in the source data will be repeated in the converted data and at the same distances from each other.

|

||

|

||

### Markov models

|

||

|

||

Text models are used for data compression, predictive input, speech recognition, and random string generation. A text model is a probability distribution of all possible strings. Let's say we have an imaginary probability distribution of the texts of all the books that humanity could ever write. To generate a string, we just take a random value with this distribution and return the resulting string (a random book that humanity could write). But how do we find out the probability distribution of all possible strings?

|

||

|

||

First, this would require too much information. There are 256^10 possible strings that are 10 bytes in length, and it would take quite a lot of memory to explicitly write a table with the probability of each string. Second, we don't have enough statistics to accurately assess the distribution.

|

||

|

||

This is why we use a probability distribution obtained from rough statistics as the text model. For example, we could calculate the probability of each letter occurring in the text and then generate strings by selecting each next letter with the same probability. This primitive model works, but the strings are still very unnatural.

|

||

|

||

To improve the model slightly, we could also make use of the conditional probability of the letter's occurrence if it is preceded by N-specific letters. N is a pre-set constant. Let's say N = 5, and we are calculating the probability of the letter "e" occurring after the letters "compr". This text model is called an Order-N Markov model.

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

P(cata | cat) = 0.8

|

||

P(catb | cat) = 0.05

|

||

P(catc | cat) = 0.1

|

||

...

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Let's look at how Markov models work on the website [of Hay Kranen](https://projects.haykranen.nl/markov/demo/). Unlike LSTM neural networks, the models only have enough memory for a small context of fixed-length N, so they generate funny nonsensical texts. Markov models are also used in primitive methods for generating spam, and the generated texts can be easily distinguished from real ones by counting statistics that don't fit the model. There is one advantage: Markov models work much faster than neural networks, which is exactly what we need.

|

||

|

||

Example for Title (our examples are in Turkish because of the data used):

|

||

|

||

<blockquote style="font-size: 15px;">

|

||

<p>Hyunday Butter'dan anket shluha — Politika head manşetleri | STALKER BOXER Çiftede book — Yanudistkarışmanlı Mı Kanal | League el Digitalika Haberler Haberleri — Haberlerisi — Hotels with Centry'ler Neden babah.com</p>

|

||

</blockquote>

|

||

|

||

We can calculate statistics from the source data, create a Markov model, and generate new data. Note that the model needs smoothing to avoid disclosing information about rare combinations in the source data, but this is not a problem. We use a combination of models from 0 to N. If statistics are insufficient for order N, the N−1 model is used instead.

|

||

|

||

But we still want to preserve the cardinality of data. In other words, if the source data had 123456 unique URL values, the result should have approximately the same number of unique values. We can use a deterministically initialized random number generator to achieve this. The easiest way is to use a hash function and apply it to the original value. In other words, we get a pseudorandom result that is explicitly determined by the original value.

|

||

|

||

Another requirement is that the source data may have many different URLs that start with the same prefix but aren't identical. For example: `https://www.clickhouse.com/images/cats/?id=xxxxxx`. We want the result to also have URLs that all start with the same prefix, but a different one. For example: http://ftp.google.kz/cgi-bin/index.phtml?item=xxxxxx. As a random number generator for generating the next character using a Markov model, we'll take a hash function from a moving window of 8 bytes at the specified position (instead of taking it from the entire string).

|

||

|

||

<pre class='code-with-play'>

|

||

<div class='code'>

|

||

https://www.clickhouse.com/images/cats/?id=12345

|

||

^^^^^^^^

|

||

|

||

distribution: [aaaa][b][cc][dddd][e][ff][ggggg][h]...

|

||

hash("images/c") % total_count: ^

|

||

</div>

|

||

</pre>

|

||

|

||

It turns out to be exactly what we need. Here's the example of page titles:

|

||

|

||

<pre class='code-with-play'>

|

||

<div class='code'>

|

||

PhotoFunia - Haber7 - Have mükemment.net Oynamak içinde şaşıracak haber, Oyunu Oynanılmaz • apród.hu kínálatában - RT Arabic

|

||

PhotoFunia - Kinobar.Net - apród: Ingyenes | Posti

|

||

PhotoFunia - Peg Perfeo - Castika, Sıradışı Deniz Lokoning Your Code, sire Eminema.tv/

|

||

PhotoFunia - TUT.BY - Your Ayakkanın ve Son Dakika Spor,

|

||

PhotoFunia - big film izle, Del Meireles offilim, Samsung DealeXtreme Değerler NEWSru.com.tv, Smotri.com Mobile yapmak Okey

|

||

PhotoFunia 5 | Galaxy, gt, după ce anal bilgi yarak Ceza RE050A V-Stranç

|

||

PhotoFunia :: Miami olacaksını yerel Haberler Oyun Young video

|

||

PhotoFunia Monstelli'nin En İyi kisa.com.tr –Star Thunder Ekranı

|

||

PhotoFunia Seks - Politika,Ekonomi,Spor GTA SANAYİ VE

|

||

PhotoFunia Taker-Rating Star TV Resmi Söylenen Yatağa każdy dzież wierzchnie

|

||

PhotoFunia TourIndex.Marketime oyunu Oyna Geldolları Mynet Spor,Magazin,Haberler yerel Haberleri ve Solvia, korkusuz Ev SahneTv

|

||

PhotoFunia todo in the Gratis Perky Parti'nin yapıyı by fotogram

|

||

PhotoFunian Dünyasın takımız halles en kulları - TEZ

|

||

</div>

|

||

</pre>

|

||

|

||

## Results

|

||

|

||

After trying four methods, I got so tired of this problem that it was time just to choose something, make it into a usable tool, and announce the solution. I chose the solution that uses random permutations and Markov models parametrized by a key. It is implemented as the clickhouse-obfuscator program, which is very easy to use. The input is a table dump in any supported format (such as CSV or JSONEachRow), and the command line parameters specify the table structure (column names and types) and the secret key (any string, which you can forget immediately after use). The output is the same number of rows of obfuscated data.

|

||

|

||

The program is installed with `clickhouse-client`, has no dependencies, and works on almost any flavor of Linux. You can apply it to any database dump, not just ClickHouse. For instance, you can generate test data from MySQL or PostgreSQL databases or create development databases that are similar to your production databases.

|

||

|

||

```bash

|

||

clickhouse-obfuscator \

|

||

--seed "$(head -c16 /dev/urandom | base64)" \

|

||

--input-format TSV --output-format TSV \

|

||

--structure 'CounterID UInt32, URLDomain String, \

|

||

URL String, SearchPhrase String, Title String' \

|

||

< table.tsv > result.tsv

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```bash

|

||

clickhouse-obfuscator --help

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Of course, everything isn't so cut and dry because data transformed by this program is almost completely reversible. The question is whether it is possible to perform the reverse transformation without knowing the key. If the transformation used a cryptographic algorithm, this operation would be as difficult as a brute-force search. Although the transformation uses some cryptographic primitives, they are not used in the correct way, and the data is susceptible to certain methods of analysis. To avoid problems, these issues are covered in the documentation for the program (access it using --help).

|

||

|

||

In the end, we transformed the data set we needed [for functional and performance testing](https://clickhouse.com/docs/en/getting-started/example-datasets/metrica/), and received approval from our data security team to publish.

|

||

|

||

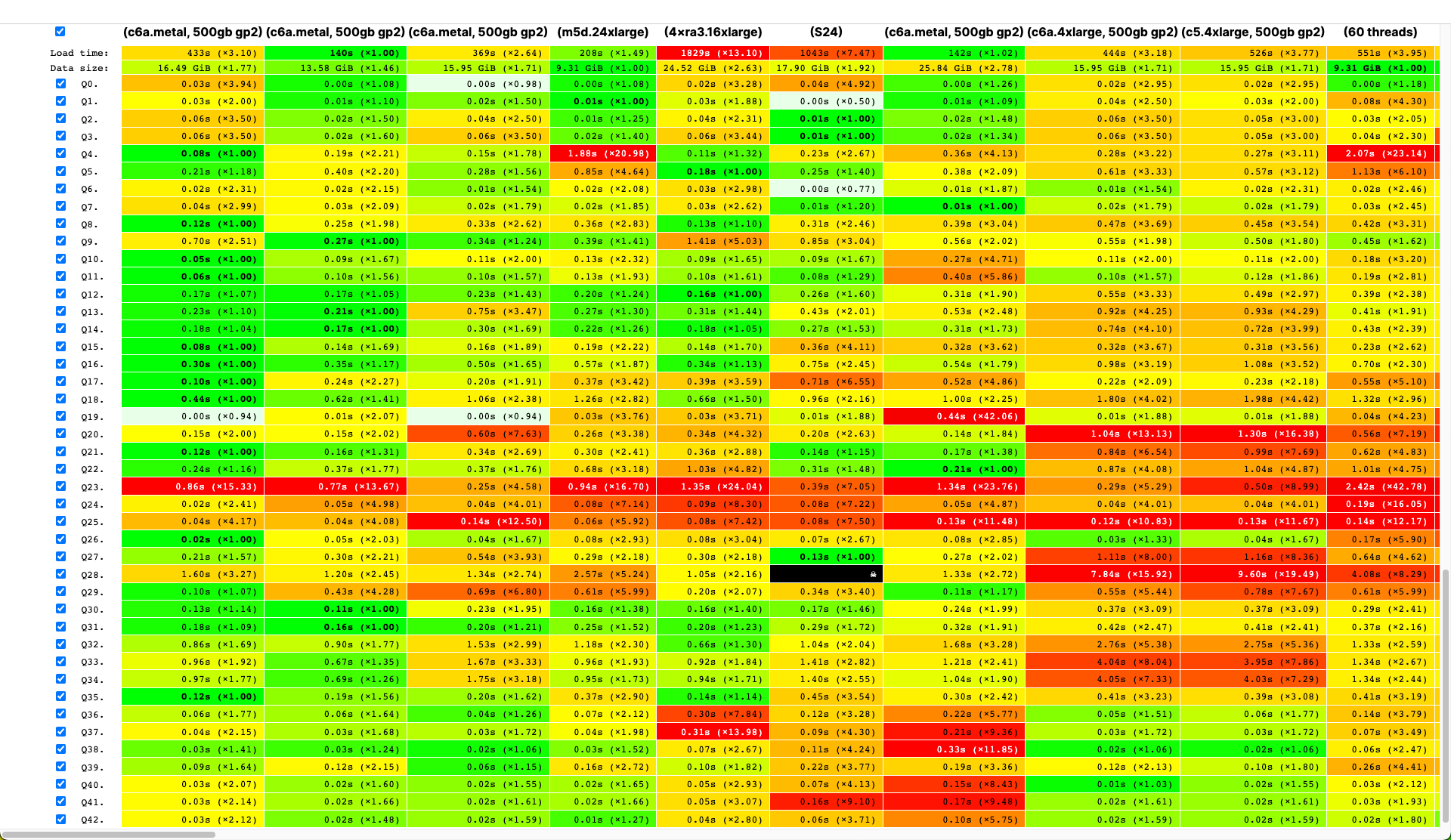

Our developers and members of our community use this data for real performance testing when optimizing algorithms inside ClickHouse. Third-party users can provide us with their obfuscated data so that we can make ClickHouse even faster for them. We also released an independent open benchmark for hardware and cloud providers on top of this data: [https://benchmark.clickhouse.com/](https://benchmark.clickhouse.com/)

|